S. E. Gontarski interview 1988

Alexander Laurence, «The Portable Infinite»

March 22, 1988 2:45pm. Stan Gontarski is a writer and a director of plays of many Samuel Beckett’s plays including Ohio Impromptu, What Where, Company, and Happy Days. His books include Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days: A Manuscript Study and The Intent of Undoing in Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Texts. He also edited the book On Beckett: Essays and Criticism.

On April 12 and 13th 1988 he will take part in the 23rd Annual Comparative Literature Conference, this year’s subject being the grotesque in literature and art, in the Multipurpose Room in the Student Union. Sessions will be taking place all day on both days. Tuesday night at 7 pm a screening of Marat/Sade will occur, and Wednesday night at 7 pm Frederick Burwick will give a special slide-lecture. Other lectures will include Raymond Lacoste on ‘Marketplace Grotesques’ and Frank Fata on Rabelais’ vision of the bodily grotesque. Gontarski will be showing a film of Beckett’s What Where which will be its American premiere. It will show at 10 am both days. April 13 is Beckett’s 82nd birthday.

Alexander Laurence: I wanted you to talk about how you first became interested in Samuel Beckett out of all of these writers.

Stan Gontarski: Well the interest has been there for a long time. I grew up in New York with an interest in theater at about the time that Alan Schneider was directing some interesting works off-Broadway, and I saw some of the original productions he did like Krapp’s Last Tape. I was very attracted to that work then, but it wasn’t really until I got to graduate school that I had a scholarly interest in Beckett’s work. Some of that rose out of just finding a whole batch of manuscripts at Ohio State University which nobody was particularly interested in working on, and so, I did.

The only manuscripts that Beckett still has are, I think, Molloy and Waiting for Godot. Maybe some of his new work?

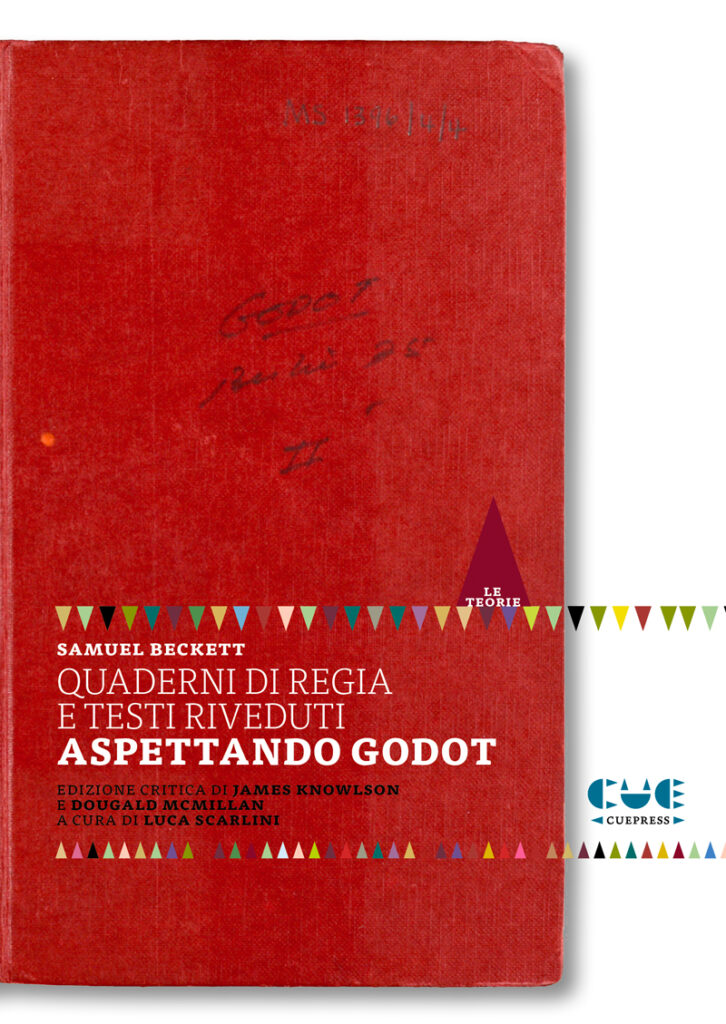

I think just Godot is all he held on to. The rest he’s given away, sold, generally gotten rid of. He likes to keep his desk clean. But it wasn’t until graduate school that I had a scholarly interest in it.

What years are these? Late sixties?

Yes, late sixties. I started a dissertation around 1972 or so. And that lead, because there was a lot of original material that I was working on, that lead to some contact with Beckett through some friends. And that just grew over the years. I got lucky enough to work with him on a couple of creative projects. We started out just his answering basic questions about his manuscripts, and dating things and the like, and by the eighties we started to work on various theatrical projects.

Before he had won those two prizes: the one in 1961 which he won with Borges…

Borges, yes. That was a short-lived international prize offered by some radical publishers, Barney Rosset of Grove Press among them. That did not last too long. But he and Borges shared the prize in ’61?

Yes ’61, and the other prize…

The Nobel Prize in ’69.

Was he being taken very serious before? was there things being written about his work before the sixties?

I think there was an interest in his work through the fifties, but it was fairly small. Things certainly did explode with the Nobel Prize. That gave him a kind of legitimacy. And a couple of key books, I mean some key critics deciding to turn their attention to Beckett certainly gave him an academic legitimacy; Hugh Kenner among them. Hugh Kenner’s book on Beckett I guess comes out about 1961, the first one out of Grove Press. So he’s in there pretty early, certainly before the kind of international recognition of those two prizes suggest.

And before that most of the people who were writing about Beckett were writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet…

Well, certainly the French had discovered him pretty early.

Blanchot, Bataille, and Robbe-Grillet were writing about him early on, and then the critics finally caught up.

Well, part of the difference of course is that he was immediately available to the French; it took a few years for that to get translated and published in the United States. So people like Blanchot and Bataille are writing about the trilogy of novels as soon as they come out in the early fifties.

What was the impact on those novels?

Well, it was very small. I think the French had an early enthusiasm for Beckett that sort of died out after the fifties. And in America, people start writing about him in 1955 or so, as the novels are coming out, as Godot is done in this country. But that progress is fairly slow, but the progression has moved almost geometrically. I pity a graduate student who is going to turn his attention to Beckett’s work because the amount of material published on him is just enormous. He is clearly the most written about living writer, and certainly among the four or five most written about people in the world. I mean John Calder, his British publisher, had argued that the most written about people are Christ, Napoleon, Wagner, and the literary people right behind that: Dickens and Joyce. Beckett is right with them. So there’s been an incredible amount of stuff.

Did Beckett inspire, along with Sarraute and Robbe-Grillet, the books that came out of Editions de Minuit?

I think, at any rate, the person who took over that publishing company after the war, Jerome Lindon, was interested in publishing some radical people; and when Suzanne Beckett brought the manuscript to Lindon evidently he liked it immediately and accepted the publication of that, and the whole trilogy of novels. And so during that time he was publishing all those people who became part of the ‘Nouveau Roman’: Sarraute, Duras, Robbe-Grillet…

When did you eventually meet Beckett? What year?

In the early seventies, I cannot remember the exact year. I guess it was summer 1975 because there were a number of failures… We had some correspondence, and he said “when you come over to Paris we’ll get together for coffee”. I went over that first summer and dropped him a note, and got a very kind note back which said sorry, he’s very tied up, and could not meet with me, but the next time I was in Paris we would surely meet. And I did faithfully come back the next year and wrote the note again saying “I’m in Paris now, do you have time for a coffee?”. And I got another note back the second year saying “Really very tied up, can’t possibly meet with you now, but if you return the next year we will surely meet.” So I think it was actually ’73, my third time, in Paris that we finally did meet.

Why did Susan Sontag and Allen Ginsburg get to meet Beckett the first time?

For one, Beckett already had an appointment with John Calder, at that meeting in Berlin. They sort of tagged along. Calder thought Beckett would be interested in meeting all these people. So Burroughs, Ginsburg, and Susan Sontag all trucked over to the institute of art in Berlin where Beckett was staying while he directed a production of, I guess, Godot. And they all had a more or less uncomfortable afternoon in Beckett’s rooms.

Did you ever meet Deidre Bair? (Author of the Beckett biography)

We’ve met a few times.

When she was doing her book?

She was doing her book for quite some time. I don’t remember when it comes out. Maybe ’74 or ’75. She was working on that as a doctoral dissertation out of Columbia during that time. And she was very lucky in that she found someone who had a whole cache of letters that Beckett had written to his friend Thomas MacGreevy: over 600 letters about all his personal problems during about a twenty year period. So that was a monumental find, and the basis of that biography. But the biography has a strange place: it was praised incredibly by the popular press, and damned almost uniformly by the scholarly press. In that, Richard Ellmann wrote the review in the New York Review of Books which blasted it pretty strongly.

On what grounds?

Well, mostly inaccuracies. The book is filled with conjectures; and my own feeling is that it’s fine while she sticks to those 600 letters, after that it gets very chancy.

When she starts interpreting the plays?

Her analysis of literature is not very good.

Why did she have to get into books?

I ask myself that same question. I’m not sure why.

What would a meeting with Beckett be like?

Well, I was admittedly terrorized by this first meeting because you got this monumental figure already by then. He has won the Nobel prize a few years before, was a really good friend of James Joyce, and the thought of this fellow palling around and chatting with Joyce and everyone who moved in that circle in the late 20’s.

And Pound.

He met Pound, but they did not get along all that well.

There is a good story about Pound and Beckett in Bair’s biography where Pound asked Beckett if «he was going to write the new Iliad?»

That sounds like Pound. Right. And Beckett was doing the opposite. But at any rate, one has all these images in one’s mind about Beckett’s status. It was really tense, for me, it was a tense first meeting.

It was more tense than meeting Hugh Kenner?

Oh yes. I mean, I have a great deal of respect fo Kenner, but he has not transformed Western literature the way Beckett has. So, I think the first time we met, there were a lot of long pauses, not a lot to be said, and a lot of wondering what I was doing there. And a few years later, the British publisher, John Calder, for various reasons which I still do not understand, wrote up that story for the Manchester Guardian. I guess it is the start of my biography. And in Calder’s version, evidently we didn’t say anything for the course of a full hour. I don’t remember it exactly like that. My version is a little bit different. But it was at least very awkward. And generally I realized that instead of sitting around talking about Existential philosophy and the plight of the world, that Beckett was interested in having a cup of coffee and chit-chatting about various types of things, including what I was doing, and what other people were writing, and what we were doing in the theater and the like. He seemed to have a genuine interest in all of that. The meetings from there on became more and more cordial, and more of those meetings we began to talk about theater rather than literary research, which is how we started talking about my doing some of his work: my directing some of his work.

I always wondered what Beckett thought of Antonin Artaud?

I’m sure that Beckett was interested in all of that, but I think his theater tends to be very different from that of Artaud’s, I mean, that whole theory of the theatrer of cruelty, that idea of intense emotion, Beckett recoils from all of that. His theater tends to be more stylized, much more, one of his favorite words is ‘balladic’.

When did you start directing Beckett’s plays?

Well, I had done some as a graduate student on an amateur level.

Which ones were those?

I did Krapp’s Last Tape. Very early on I did a production of Endgame as an undergraduate. But it is not until the 1980’s that I return to professional theater myself and started working with Beckett on some projects. When I was a Ohio State, we ran a conference to celebrate his 75th anniversary, and I talked him into writing a little play so that we could put on a world premiere: sort of his giving us a birthday present. And he wrote Ohio Impromptu. And that really got me back into theater. I didn’t direct that, but I produced it, and got Alan Schneider and the man who’s become a famous Beckett actor now, David Warrilow, together. We did that production at Ohio State. Well, that went on and toured all over the world. That was a very interesting, important production. And that sort of wetted my appetite for getting back into theater. So a few years later I worked with him on an adaptation of a prose work called Company.

Which played in Los Angeles.

I directed it at the Los Angeles Actor Theater which is the precursor of the Los Angeles Theater Center.

How was Beckett involved in this production?

Well, I was in Paris at the time, and I was working with the French director Pierre Chabert, and Beckett would come to rehearsals. So we would sit after rehearsals and talk about how the French production was going, and how we would change the production in English. It was at those meetings after rehearsals that we worked out what the English text should be, how the production in English should differ, and how to create, what seemed to be, some of the errors of the French production. So I did that in Los Angeles, and we took that to a festival in Madrid right after it. A couple of years after that I was living in Paris working with him on various projects when he rewrote What Where.

That is What Where I and What Where II.

Well, those are my designations just to separate them. I wrote an article which talks about What Where II. Beckett hasn’t made those sort of distinctions. What he did do was he wrote a play in the early 1980’s called What Where which had a particular stage pattern and then he was invited in 1985 to go to Stuttgart to do a television production and he decided to rewrite this play, and really radically changed it. After having done that, for West German television, he decided that he liked that version better than the original version. When some people in France asked him for a play as part of the 80th birthday celebration he said «why not do a stage adaptation of this now transformed play What Where». And so they made a few more changes for the French stage presentation. I was again in Paris at the time and at rehearsals, and did essentially the same thing: talked to Beckett about what kind of changes we would make for an American production. And then brought that back to the United States in the Fall of 1986, and did it at the Magic Theater in San Francisco as part of an evening of four one-act plays. That production then was filmed for television by a group called Global Village. And so re-translated, this play, which was originally a stage play, then a television play, then a stage play again in English in San Francisco, re-did it for television. So whether that’s What Where II or What Where IV, I’m not sure. But it’s a radically re-done version from the original stage play and the printed script. And it’s that version that’s going to be shown at 23rd Annual Comparative Literature Conference on campus here on April 12 and 13.

And after we see it, you are going to talk about it?

Yes, if anyone is interested in talking about it. It’s a very short production: it’s only about ten minutes long. So we will be able to look at the videotape, and either I will talk or we will have a panel discussion.

You have also done Beckett’s Happy Days this year. When did that start up?

What happened is when I did this What Where at the Magic Theater (and the reason I went to the Magic Theater is that my good friend Martin Esslin is the dramaturg there), so I had this newly revised play by Beckett and was looking for an American producer and he suggested that it would be good to do it at the Magic Theater because they were celebrating their 20th anniversary in 1986. So that went pretty well, the reviews were good. So they asked me to come back the following year to do another production and that was this past year. I squeezed in a production of Happy Days between the fall semester and the winter semester here. There is just enough time to shoot up to San Francisco and get in five weeks of rehearsals and open the play shoot back here for the beginning of classes at the end of January.

Go back on week-ends?

Back on week-ends to check for creative deviations. But that production went pretty well too. It was well received by the press, so they asked me to come back next year and do another production. And since I have a new book coming out on Endgame with Faber and Faber in England and Grove Press in this country, they suggested I direct Endgame.That should go into rehearsals about mid-December, as soon as final exams are over for next fall’s term, and open about mid-January.

How do you approach a play like Happy Days? Is it important to make directorial decisions like bringing out a real dirt mound or is that even a possibility?

Sure, sure. I think those are one of the decisions you make as you go along: how realistic you use.

Or a papier-mache?

Well, we used a painted canvas which people have used. But we toyed with a real dirt mound.

Is that necessary?

No. I think the plays are not finally that realistic that you need to. I prefer the stylized productions myself. And my own productions of Beckett have grown out of not only my scholarly interests in these works (part of the reason John Lion at the Magic Theatre wanted me to do Happy Days was because I had written a little book about it and never directed it, so he thought that would be a nice touch, and part of the reason he wants Endgame is because I have just finished a book on that; so there’s a great deal of scholarly background behind it), but I’ve also been lucky over the years to watch Beckett direct four or five times. And I’ve gotten a great appreciation of his work for the theater although he is not trained in any of the standard directorial approaches. His approach as a director would probably appall most American directors. I mean he has a very clear sense of these plays, and he brings out an absolutely extraordinary nuance in every play. I’ve been lucky to spend weeks and weeks watching him work in the theater, and have been obviously heavily influenced by his approach in my own directing, although you can’t work like that with American actors. You can’t read them a line and say ‘do it like this’.

So for Beckett and yourself, besides the visual aspect, is there room for invention

I think so…

Or do you stay pretty close to the text, and you don’t try to add much?

I don’t think these are mutually exclusive. Yes, we do stay as letter perfect as we can because there’s something to be gained from doing this play as close as the way Beckett sees it as you can. But within that you realize that there are hundreds and hundreds of directorial decisions that finally have an affect on the play: how every line is delivered, where the emphasis falls in every line, in every syllable, the way you pronounce certain words. There are just hundreds and hundreds of day to day decisions that affect the final play. And so far there’s been plenty of creative outlet on the linguistic level because these plays are very verbal as well as being excitingly visual.

Would you approve of the distinction between a verbal theater and another which is non-verbal like Kabuki theater?

I think that there are many different kinds of theater. I think Beckett does a pretty good job of merging a highly literary, highly literate, very verbal theater with pretty exciting visual images which is why you can almost have a static theater. I mean so many of the plays which I’ve done of Beckett’s almost nobody moves.Company is a guy sitting in a chair, the whole hour. Happy Days: the woman is in a mound for an hour the first act, thirty minutes the second act. I also did Ohio Impromptu which is just two people sitting at a table; one reads the other listens. That’s the whole play. There’s not a lot of action. What’s exciting though is that the visual tableaux, which is virtually in so many of these plays almost a still life, is extremely compelling and the verbal text is magnificent. He’s the master of holding an audience with verbal nuance. So one way or another you spend an awful amount of your time in rehearsals, not with blocking action, there’s not a lot of movement, but you spend a lot time with verbal nuance.

Well, one needs to practice standing still for an hour, to get that stillness desired.

Sure.

Or the precise movement?

Exactly. And certainly a minimal amount of movement. Almost any movement becomes magnified and enormously important. So he’s done as good job as any of blending a high literary text and a visceral visual image. Now we’ve been working with some of Ionesco’s texts, and they are interesting, but I don’t think they have that high literary quality to them.

Well let’s get on. How are you going to prepare for your next production in December, Endgame?

Well, in part I have. I have just finished this book on Endgame, and it’s really extraordinary in a way because the book has a new text based on Beckett’s changes as a director, and he was very kind to go over his whole manuscript, so he made a few more changes in the text. And this text that will appear in this book is also completely annotated. So a good deal of the literary background of this production which will begin at the end of the year is all done. A lot of the directorial preparation is essentially done. The question now is to find what kind of cast you are going to have, and how you can balance your conception of the play before seeing the actors to what the actors can do, and what they’re capable of doing, and what you can get out of them. So it’s a matter of adapting all that literary material now to the strengths and weaknesses of particular actors and designers, and all the people you have to work with for this kind of production.

You talked about how Beckett revised all his texts. Endgame, Godot, Krapp’s Last Tape. He’s made cuts in all of these?

All of them!

I didn’t know.

I mean the ones he’s directed.

And John Calder is going to publish these new books?

Faber and Faber will.

Faber and Faber will publish the revised versions?

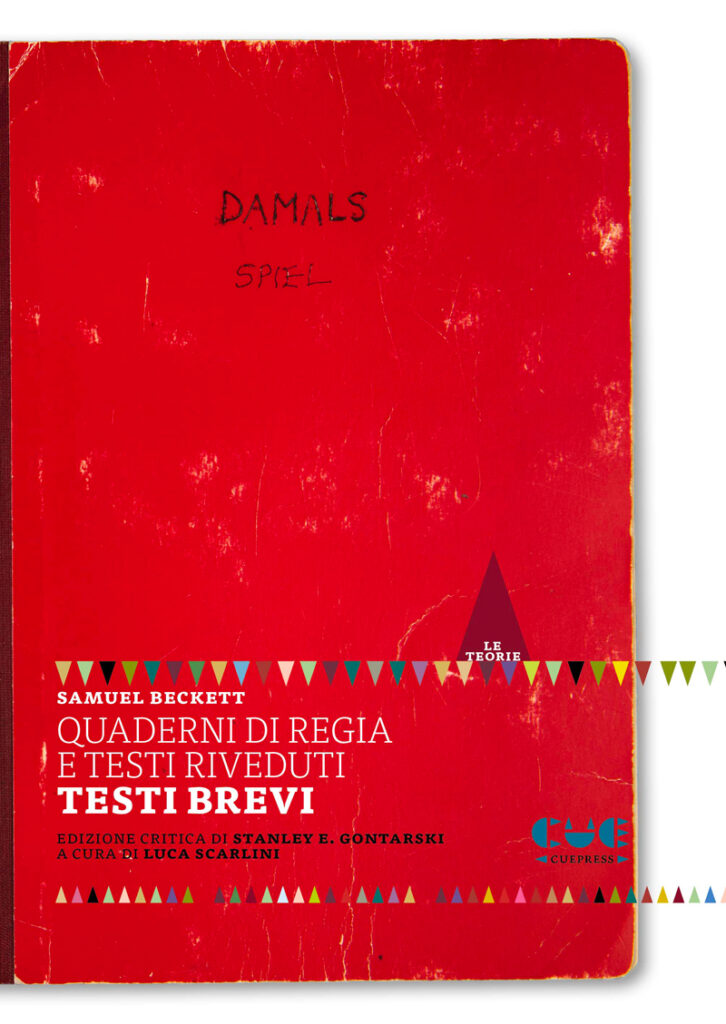

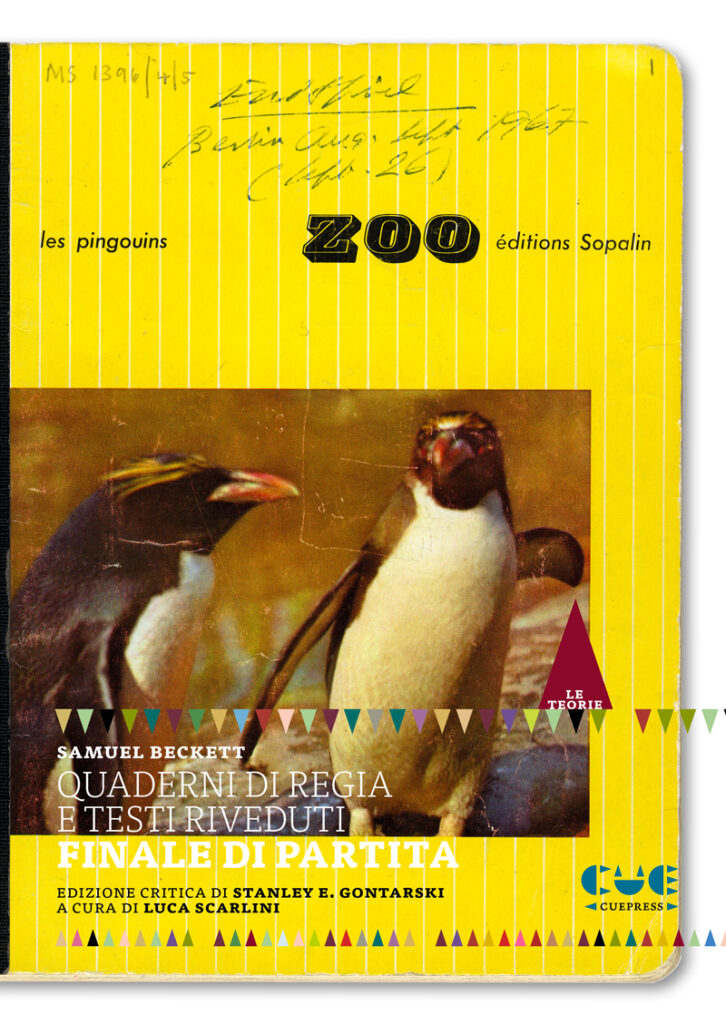

Right. First they’ll be part of a theater notebook series.

They’re publishing Beckett’s notebooks.

The notebooks with new texts, with notes and introductions. First they’ll publish those theater notebooks, and then a year after that they’ll publish all new annotated scripts.

That changes the texts scholars have been working with in the past. So that means we will all expect more critical articles dealing with the final texts.

Oh sure. Once that material is available to see how Beckett has revised his work sometimes coming back to it ten fifteen twenty years later, I’m sure that will generate a lot of academic discussion about the nature of those changes.

Beckett does not add, he just cuts.

Pretty much. It’s been a question of clearing away the unnecessary material. Cutting the fat!

Is that what all his books are about: throwing away the literary baggage?

Certainly seems to be a major theme of pairing out of all that excess. And so it is very interesting that as a director he seems to be creating a process. The process of playwriting for him is not only working on the page, but finally when he gets on the stage he has the opportunity to visualize it all, and makes changes accordingly.

Is this the first production of Endgame since maybe…

This will be the first production of Endgame in this country to use what will be from now on the revised acting text.

Beckett’s final quarto?

Should be. I don’t expect Beckett to make any more changes in the text.

Yes, I saw the Alvin Epstein production.

What did you think?

Well, I liked the sets. They looked good. It was more comical. They bought that out more. Irish accents. I saw it in a small theatre in Santa Monica, The Mayfair. I’d like to see Beckett’s German production Endspiel.

We will, I’ve got a copy of it.

So that I can compare.

We’ll see it.

I think we’ve come to the end of this interview.

OK, Good.

Let me see if I recorded anything.

Collegamenti