Logbook

Approfondimenti, interviste, recensioni e cultura: il meglio dell’editoria e delle arti da leggere, guardare e ascoltare.

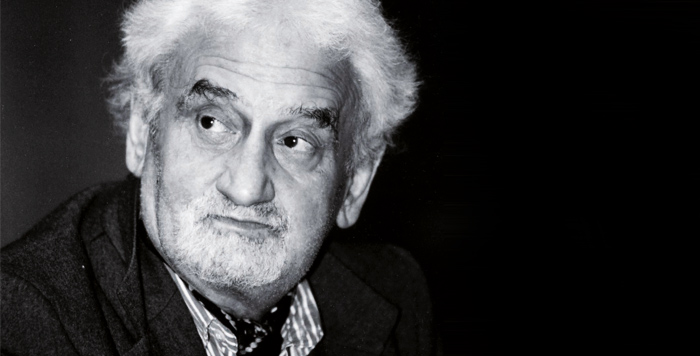

«Io, che ormai sono un miliardo di miliardi di particelle che vagano, vedo tutto e di tutto posso dar conto»: in memoria di Antonio Tarantino

Non poteva che uscirsene così: con un colpo di teatro. Lui, non i suoi scritti: quelli rimarranno e continueranno a vivere nella voce e nei movimenti e nelle regie di chi si abbevera alla fonte della parola, atto liturgico, nemesi lisergica che solo dopo la morte trova chi la pota e se ne prende cura.

Il drammaturgo Antonio Tarantino se ne è andato. Arresto cardiaco, più o meno l’effetto che ha il lampadario che alla fine del primo atto manda gli spettatori de The phantom of the Opera in pausa: improvviso, devastante, a modo suo teatrale.

Che poi Antonio Tarantino, al teatro, non ci è arrivato in età precoce: enfant prodige, alla maniera di Fausto Paradivino – e tra un po’ il perché dell’avvicinamento tra i due – non lo è stato: nato nel 1938 a Bolzano, ha dedicato buona parte della sua vita alla pittura figurativa. Poi la scintilla, l’incendio che avvampa: la scrittura per la scena. Un incontro intimo e sconvolgente, ruvido e movimentato come gli amplessi sotto le lenzuola clandestine di un cielo stellato, o sotto il tettuccio di una cabina del mare.

Nel 1994 Tarantino si aggiudica il Premio Riccione con il monologo Stabat Mater, una sorta di preghiera del XIII Secolo che diventa una freccia: Tarantino incocca il tempo e la lancia dritta dritta nel presente: la sua Maria è una ragazza-madre prostituta che si strugge nell’attesa di ricevere notizie del figlio arrestato e della figura dissoluta di suo padre. Anche questa Maria, come le tante cui tocca lo stesso sventurato destino, incrocia nella sua esistenza un Giovanni, un Ponzio Pilato, una Maddalena… La forza dell’assolo ricorda a tratti la scrittura di Dario Fo: il gramelot di Tarantino è un italiano con vibranti sporcature dialettali e gergali. Come la lingua di chi non ha studiato. Come il parlato dei diseredati, dei reietti, di chi vive nell’ombra. Che non parla: si esprime.

Fausto Paravidino nel 1998 scrive Due fratelli – tragedia da camera in 53 giorni. Con questo testo, portato in scena anche al Festival di Santarcangelo dai Motus, vince il Premio Riccione intitolato a Vittorio Tondelli nel 1999 e il premio Ubu come migliore novità italiana.

Anche su incitamento di Franco Quadri (che ha pubblicato per la sua casa editrice Ubulibri quasi tutta l’opera di Tarantino e che ha legato il suo nome al Premio Riccione), molti attori si sono cimentati con i suoi testi: nella Romagna Felix il Teatro delle Albe di Marco Martinelli ed Ermanna Montanari ha portato in scena Stranieri, in giro per l’Italia invece Piera Degli Esposti si è confrontata con lo Stabat Mater, Giorgio Albertazzi invece con La casa di Ramallah, passato sulle assi del Teatro Novelli di Rimini nel 2010 e dà vita e voce all’atroce dramma di Myriam, una kamikaze che si farà esplodere in un locale pubblico di Ramallah con la benedizione dei genitori che hanno già dato alla causa quattro figli maschi e ora aiutano lei a sistemarsi l’esplosivo intorno al corpo.

Nel 2000 il robustissimo Materiali per una tragedia tedesca, vincitore del Premio Riccione nel 1997 e Premio Ubu nel 1999-2000 come Migliore novità italiana (due riconoscimenti abbastanza ‘fratelli’¸ se non consanguinei), diventa spettacolo teatrale: il regista Cherif ne firma l’allestimento in un’ambiziosa produzione del Piccolo di Milano.

In questo menhir Antonio Tarantino ripercorre, in un kolossal da ottantacinque personaggi, uno dei periodi più complessi degli anni Settanta: lo scandalo della Germania d’autunno, le imprese della banda Baader-Meinhof, il rapimento e l’uccisione del grande industriale Schleyer, il dirottamento di un aereo della Lufthansa a Mogadiscio da parte dei fedayn di aerei, le strategie politiche violentemente del governo Schmidt e il suicidio di stato dei terroristi tedeschi nella prigione di Stammheim. Un momento buio di grave crisi politica, vissuto da un paese ricco di allarmanti ambiguità, viene ricreato con il taglio dei grandi classici in un linguaggio basso che gioca comicamente sulle tecniche del varietà, mobilitando la gente comune in un viaggio tra i continenti che si prolunga al di là della vita.

Dice la kamizake Myriam di Tarantino prima di andarsene: «Io, che ormai sono un miliardo di miliardi di particelle che vagano, vedo tutto e di tutto posso dar conto: e cioè che dio non esiste, che pace e guerra sono destinate a inseguirsi nel cerchio rovente del tempo, come s’inseguono amore e odio, salute e malattia, giorno e notte, sole e pioggia, padri e figli, noi e loro, la loro storia e la nostra: e nessuno ha ragione, completamente ragione, né completamente torto».

Sipario.

Collegamenti

S. E. Gontarski interview 1988

March 22, 1988 2:45pm. Stan Gontarski is a writer and a director of plays of many Samuel Beckett’s plays including Ohio Impromptu, What Where, Company, and Happy Days. His books include Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days: A Manuscript Study and The Intent of Undoing in Samuel Beckett’s Dramatic Texts. He also edited the book On Beckett: Essays and Criticism.

On April 12 and 13th 1988 he will take part in the 23rd Annual Comparative Literature Conference, this year’s subject being the grotesque in literature and art, in the Multipurpose Room in the Student Union. Sessions will be taking place all day on both days. Tuesday night at 7 pm a screening of Marat/Sade will occur, and Wednesday night at 7 pm Frederick Burwick will give a special slide-lecture. Other lectures will include Raymond Lacoste on ‘Marketplace Grotesques’ and Frank Fata on Rabelais’ vision of the bodily grotesque. Gontarski will be showing a film of Beckett’s What Where which will be its American premiere. It will show at 10 am both days. April 13 is Beckett’s 82nd birthday.

Alexander Laurence: I wanted you to talk about how you first became interested in Samuel Beckett out of all of these writers.

Stan Gontarski: Well the interest has been there for a long time. I grew up in New York with an interest in theater at about the time that Alan Schneider was directing some interesting works off-Broadway, and I saw some of the original productions he did like Krapp’s Last Tape. I was very attracted to that work then, but it wasn’t really until I got to graduate school that I had a scholarly interest in Beckett’s work. Some of that rose out of just finding a whole batch of manuscripts at Ohio State University which nobody was particularly interested in working on, and so, I did.

The only manuscripts that Beckett still has are, I think, Molloy and Waiting for Godot. Maybe some of his new work?

I think just Godot is all he held on to. The rest he’s given away, sold, generally gotten rid of. He likes to keep his desk clean. But it wasn’t until graduate school that I had a scholarly interest in it.

What years are these? Late sixties?

Yes, late sixties. I started a dissertation around 1972 or so. And that lead, because there was a lot of original material that I was working on, that lead to some contact with Beckett through some friends. And that just grew over the years. I got lucky enough to work with him on a couple of creative projects. We started out just his answering basic questions about his manuscripts, and dating things and the like, and by the eighties we started to work on various theatrical projects.

Before he had won those two prizes: the one in 1961 which he won with Borges…

Borges, yes. That was a short-lived international prize offered by some radical publishers, Barney Rosset of Grove Press among them. That did not last too long. But he and Borges shared the prize in ’61?

Yes ’61, and the other prize…

The Nobel Prize in ’69.

Was he being taken very serious before? was there things being written about his work before the sixties?

I think there was an interest in his work through the fifties, but it was fairly small. Things certainly did explode with the Nobel Prize. That gave him a kind of legitimacy. And a couple of key books, I mean some key critics deciding to turn their attention to Beckett certainly gave him an academic legitimacy; Hugh Kenner among them. Hugh Kenner’s book on Beckett I guess comes out about 1961, the first one out of Grove Press. So he’s in there pretty early, certainly before the kind of international recognition of those two prizes suggest.

And before that most of the people who were writing about Beckett were writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet…

Well, certainly the French had discovered him pretty early.

Blanchot, Bataille, and Robbe-Grillet were writing about him early on, and then the critics finally caught up.

Well, part of the difference of course is that he was immediately available to the French; it took a few years for that to get translated and published in the United States. So people like Blanchot and Bataille are writing about the trilogy of novels as soon as they come out in the early fifties.

What was the impact on those novels?

Well, it was very small. I think the French had an early enthusiasm for Beckett that sort of died out after the fifties. And in America, people start writing about him in 1955 or so, as the novels are coming out, as Godot is done in this country. But that progress is fairly slow, but the progression has moved almost geometrically. I pity a graduate student who is going to turn his attention to Beckett’s work because the amount of material published on him is just enormous. He is clearly the most written about living writer, and certainly among the four or five most written about people in the world. I mean John Calder, his British publisher, had argued that the most written about people are Christ, Napoleon, Wagner, and the literary people right behind that: Dickens and Joyce. Beckett is right with them. So there’s been an incredible amount of stuff.

Did Beckett inspire, along with Sarraute and Robbe-Grillet, the books that came out of Editions de Minuit?

I think, at any rate, the person who took over that publishing company after the war, Jerome Lindon, was interested in publishing some radical people; and when Suzanne Beckett brought the manuscript to Lindon evidently he liked it immediately and accepted the publication of that, and the whole trilogy of novels. And so during that time he was publishing all those people who became part of the ‘Nouveau Roman’: Sarraute, Duras, Robbe-Grillet…

When did you eventually meet Beckett? What year?

In the early seventies, I cannot remember the exact year. I guess it was summer 1975 because there were a number of failures… We had some correspondence, and he said “when you come over to Paris we’ll get together for coffee”. I went over that first summer and dropped him a note, and got a very kind note back which said sorry, he’s very tied up, and could not meet with me, but the next time I was in Paris we would surely meet. And I did faithfully come back the next year and wrote the note again saying “I’m in Paris now, do you have time for a coffee?”. And I got another note back the second year saying “Really very tied up, can’t possibly meet with you now, but if you return the next year we will surely meet.” So I think it was actually ’73, my third time, in Paris that we finally did meet.

Why did Susan Sontag and Allen Ginsburg get to meet Beckett the first time?

For one, Beckett already had an appointment with John Calder, at that meeting in Berlin. They sort of tagged along. Calder thought Beckett would be interested in meeting all these people. So Burroughs, Ginsburg, and Susan Sontag all trucked over to the institute of art in Berlin where Beckett was staying while he directed a production of, I guess, Godot. And they all had a more or less uncomfortable afternoon in Beckett’s rooms.

Did you ever meet Deidre Bair? (Author of the Beckett biography)

We’ve met a few times.

When she was doing her book?

She was doing her book for quite some time. I don’t remember when it comes out. Maybe ’74 or ’75. She was working on that as a doctoral dissertation out of Columbia during that time. And she was very lucky in that she found someone who had a whole cache of letters that Beckett had written to his friend Thomas MacGreevy: over 600 letters about all his personal problems during about a twenty year period. So that was a monumental find, and the basis of that biography. But the biography has a strange place: it was praised incredibly by the popular press, and damned almost uniformly by the scholarly press. In that, Richard Ellmann wrote the review in the New York Review of Books which blasted it pretty strongly.

On what grounds?

Well, mostly inaccuracies. The book is filled with conjectures; and my own feeling is that it’s fine while she sticks to those 600 letters, after that it gets very chancy.

When she starts interpreting the plays?

Her analysis of literature is not very good.

Why did she have to get into books?

I ask myself that same question. I’m not sure why.

What would a meeting with Beckett be like?

Well, I was admittedly terrorized by this first meeting because you got this monumental figure already by then. He has won the Nobel prize a few years before, was a really good friend of James Joyce, and the thought of this fellow palling around and chatting with Joyce and everyone who moved in that circle in the late 20’s.

And Pound.

He met Pound, but they did not get along all that well.

There is a good story about Pound and Beckett in Bair’s biography where Pound asked Beckett if «he was going to write the new Iliad?»

That sounds like Pound. Right. And Beckett was doing the opposite. But at any rate, one has all these images in one’s mind about Beckett’s status. It was really tense, for me, it was a tense first meeting.

It was more tense than meeting Hugh Kenner?

Oh yes. I mean, I have a great deal of respect fo Kenner, but he has not transformed Western literature the way Beckett has. So, I think the first time we met, there were a lot of long pauses, not a lot to be said, and a lot of wondering what I was doing there. And a few years later, the British publisher, John Calder, for various reasons which I still do not understand, wrote up that story for the Manchester Guardian. I guess it is the start of my biography. And in Calder’s version, evidently we didn’t say anything for the course of a full hour. I don’t remember it exactly like that. My version is a little bit different. But it was at least very awkward. And generally I realized that instead of sitting around talking about Existential philosophy and the plight of the world, that Beckett was interested in having a cup of coffee and chit-chatting about various types of things, including what I was doing, and what other people were writing, and what we were doing in the theater and the like. He seemed to have a genuine interest in all of that. The meetings from there on became more and more cordial, and more of those meetings we began to talk about theater rather than literary research, which is how we started talking about my doing some of his work: my directing some of his work.

I always wondered what Beckett thought of Antonin Artaud?

I’m sure that Beckett was interested in all of that, but I think his theater tends to be very different from that of Artaud’s, I mean, that whole theory of the theatrer of cruelty, that idea of intense emotion, Beckett recoils from all of that. His theater tends to be more stylized, much more, one of his favorite words is ‘balladic’.

When did you start directing Beckett’s plays?

Well, I had done some as a graduate student on an amateur level.

Which ones were those?

I did Krapp’s Last Tape. Very early on I did a production of Endgame as an undergraduate. But it is not until the 1980’s that I return to professional theater myself and started working with Beckett on some projects. When I was a Ohio State, we ran a conference to celebrate his 75th anniversary, and I talked him into writing a little play so that we could put on a world premiere: sort of his giving us a birthday present. And he wrote Ohio Impromptu. And that really got me back into theater. I didn’t direct that, but I produced it, and got Alan Schneider and the man who’s become a famous Beckett actor now, David Warrilow, together. We did that production at Ohio State. Well, that went on and toured all over the world. That was a very interesting, important production. And that sort of wetted my appetite for getting back into theater. So a few years later I worked with him on an adaptation of a prose work called Company.

Which played in Los Angeles.

I directed it at the Los Angeles Actor Theater which is the precursor of the Los Angeles Theater Center.

How was Beckett involved in this production?

Well, I was in Paris at the time, and I was working with the French director Pierre Chabert, and Beckett would come to rehearsals. So we would sit after rehearsals and talk about how the French production was going, and how we would change the production in English. It was at those meetings after rehearsals that we worked out what the English text should be, how the production in English should differ, and how to create, what seemed to be, some of the errors of the French production. So I did that in Los Angeles, and we took that to a festival in Madrid right after it. A couple of years after that I was living in Paris working with him on various projects when he rewrote What Where.

That is What Where I and What Where II.

Well, those are my designations just to separate them. I wrote an article which talks about What Where II. Beckett hasn’t made those sort of distinctions. What he did do was he wrote a play in the early 1980’s called What Where which had a particular stage pattern and then he was invited in 1985 to go to Stuttgart to do a television production and he decided to rewrite this play, and really radically changed it. After having done that, for West German television, he decided that he liked that version better than the original version. When some people in France asked him for a play as part of the 80th birthday celebration he said «why not do a stage adaptation of this now transformed play What Where». And so they made a few more changes for the French stage presentation. I was again in Paris at the time and at rehearsals, and did essentially the same thing: talked to Beckett about what kind of changes we would make for an American production. And then brought that back to the United States in the Fall of 1986, and did it at the Magic Theater in San Francisco as part of an evening of four one-act plays. That production then was filmed for television by a group called Global Village. And so re-translated, this play, which was originally a stage play, then a television play, then a stage play again in English in San Francisco, re-did it for television. So whether that’s What Where II or What Where IV, I’m not sure. But it’s a radically re-done version from the original stage play and the printed script. And it’s that version that’s going to be shown at 23rd Annual Comparative Literature Conference on campus here on April 12 and 13.

And after we see it, you are going to talk about it?

Yes, if anyone is interested in talking about it. It’s a very short production: it’s only about ten minutes long. So we will be able to look at the videotape, and either I will talk or we will have a panel discussion.

You have also done Beckett’s Happy Days this year. When did that start up?

What happened is when I did this What Where at the Magic Theater (and the reason I went to the Magic Theater is that my good friend Martin Esslin is the dramaturg there), so I had this newly revised play by Beckett and was looking for an American producer and he suggested that it would be good to do it at the Magic Theater because they were celebrating their 20th anniversary in 1986. So that went pretty well, the reviews were good. So they asked me to come back the following year to do another production and that was this past year. I squeezed in a production of Happy Days between the fall semester and the winter semester here. There is just enough time to shoot up to San Francisco and get in five weeks of rehearsals and open the play shoot back here for the beginning of classes at the end of January.

Go back on week-ends?

Back on week-ends to check for creative deviations. But that production went pretty well too. It was well received by the press, so they asked me to come back next year and do another production. And since I have a new book coming out on Endgame with Faber and Faber in England and Grove Press in this country, they suggested I direct Endgame.That should go into rehearsals about mid-December, as soon as final exams are over for next fall’s term, and open about mid-January.

How do you approach a play like Happy Days? Is it important to make directorial decisions like bringing out a real dirt mound or is that even a possibility?

Sure, sure. I think those are one of the decisions you make as you go along: how realistic you use.

Or a papier-mache?

Well, we used a painted canvas which people have used. But we toyed with a real dirt mound.

Is that necessary?

No. I think the plays are not finally that realistic that you need to. I prefer the stylized productions myself. And my own productions of Beckett have grown out of not only my scholarly interests in these works (part of the reason John Lion at the Magic Theatre wanted me to do Happy Days was because I had written a little book about it and never directed it, so he thought that would be a nice touch, and part of the reason he wants Endgame is because I have just finished a book on that; so there’s a great deal of scholarly background behind it), but I’ve also been lucky over the years to watch Beckett direct four or five times. And I’ve gotten a great appreciation of his work for the theater although he is not trained in any of the standard directorial approaches. His approach as a director would probably appall most American directors. I mean he has a very clear sense of these plays, and he brings out an absolutely extraordinary nuance in every play. I’ve been lucky to spend weeks and weeks watching him work in the theater, and have been obviously heavily influenced by his approach in my own directing, although you can’t work like that with American actors. You can’t read them a line and say ‘do it like this’.

So for Beckett and yourself, besides the visual aspect, is there room for invention

I think so…

Or do you stay pretty close to the text, and you don’t try to add much?

I don’t think these are mutually exclusive. Yes, we do stay as letter perfect as we can because there’s something to be gained from doing this play as close as the way Beckett sees it as you can. But within that you realize that there are hundreds and hundreds of directorial decisions that finally have an affect on the play: how every line is delivered, where the emphasis falls in every line, in every syllable, the way you pronounce certain words. There are just hundreds and hundreds of day to day decisions that affect the final play. And so far there’s been plenty of creative outlet on the linguistic level because these plays are very verbal as well as being excitingly visual.

Would you approve of the distinction between a verbal theater and another which is non-verbal like Kabuki theater?

I think that there are many different kinds of theater. I think Beckett does a pretty good job of merging a highly literary, highly literate, very verbal theater with pretty exciting visual images which is why you can almost have a static theater. I mean so many of the plays which I’ve done of Beckett’s almost nobody moves.Company is a guy sitting in a chair, the whole hour. Happy Days: the woman is in a mound for an hour the first act, thirty minutes the second act. I also did Ohio Impromptu which is just two people sitting at a table; one reads the other listens. That’s the whole play. There’s not a lot of action. What’s exciting though is that the visual tableaux, which is virtually in so many of these plays almost a still life, is extremely compelling and the verbal text is magnificent. He’s the master of holding an audience with verbal nuance. So one way or another you spend an awful amount of your time in rehearsals, not with blocking action, there’s not a lot of movement, but you spend a lot time with verbal nuance.

Well, one needs to practice standing still for an hour, to get that stillness desired.

Sure.

Or the precise movement?

Exactly. And certainly a minimal amount of movement. Almost any movement becomes magnified and enormously important. So he’s done as good job as any of blending a high literary text and a visceral visual image. Now we’ve been working with some of Ionesco’s texts, and they are interesting, but I don’t think they have that high literary quality to them.

Well let’s get on. How are you going to prepare for your next production in December, Endgame?

Well, in part I have. I have just finished this book on Endgame, and it’s really extraordinary in a way because the book has a new text based on Beckett’s changes as a director, and he was very kind to go over his whole manuscript, so he made a few more changes in the text. And this text that will appear in this book is also completely annotated. So a good deal of the literary background of this production which will begin at the end of the year is all done. A lot of the directorial preparation is essentially done. The question now is to find what kind of cast you are going to have, and how you can balance your conception of the play before seeing the actors to what the actors can do, and what they’re capable of doing, and what you can get out of them. So it’s a matter of adapting all that literary material now to the strengths and weaknesses of particular actors and designers, and all the people you have to work with for this kind of production.

You talked about how Beckett revised all his texts. Endgame, Godot, Krapp’s Last Tape. He’s made cuts in all of these?

All of them!

I didn’t know.

I mean the ones he’s directed.

And John Calder is going to publish these new books?

Faber and Faber will.

Faber and Faber will publish the revised versions?

Right. First they’ll be part of a theater notebook series.

They’re publishing Beckett’s notebooks.

The notebooks with new texts, with notes and introductions. First they’ll publish those theater notebooks, and then a year after that they’ll publish all new annotated scripts.

That changes the texts scholars have been working with in the past. So that means we will all expect more critical articles dealing with the final texts.

Oh sure. Once that material is available to see how Beckett has revised his work sometimes coming back to it ten fifteen twenty years later, I’m sure that will generate a lot of academic discussion about the nature of those changes.

Beckett does not add, he just cuts.

Pretty much. It’s been a question of clearing away the unnecessary material. Cutting the fat!

Is that what all his books are about: throwing away the literary baggage?

Certainly seems to be a major theme of pairing out of all that excess. And so it is very interesting that as a director he seems to be creating a process. The process of playwriting for him is not only working on the page, but finally when he gets on the stage he has the opportunity to visualize it all, and makes changes accordingly.

Is this the first production of Endgame since maybe…

This will be the first production of Endgame in this country to use what will be from now on the revised acting text.

Beckett’s final quarto?

Should be. I don’t expect Beckett to make any more changes in the text.

Yes, I saw the Alvin Epstein production.

What did you think?

Well, I liked the sets. They looked good. It was more comical. They bought that out more. Irish accents. I saw it in a small theatre in Santa Monica, The Mayfair. I’d like to see Beckett’s German production Endspiel.

We will, I’ve got a copy of it.

So that I can compare.

We’ll see it.

I think we’ve come to the end of this interview.

OK, Good.

Let me see if I recorded anything.

Collegamenti

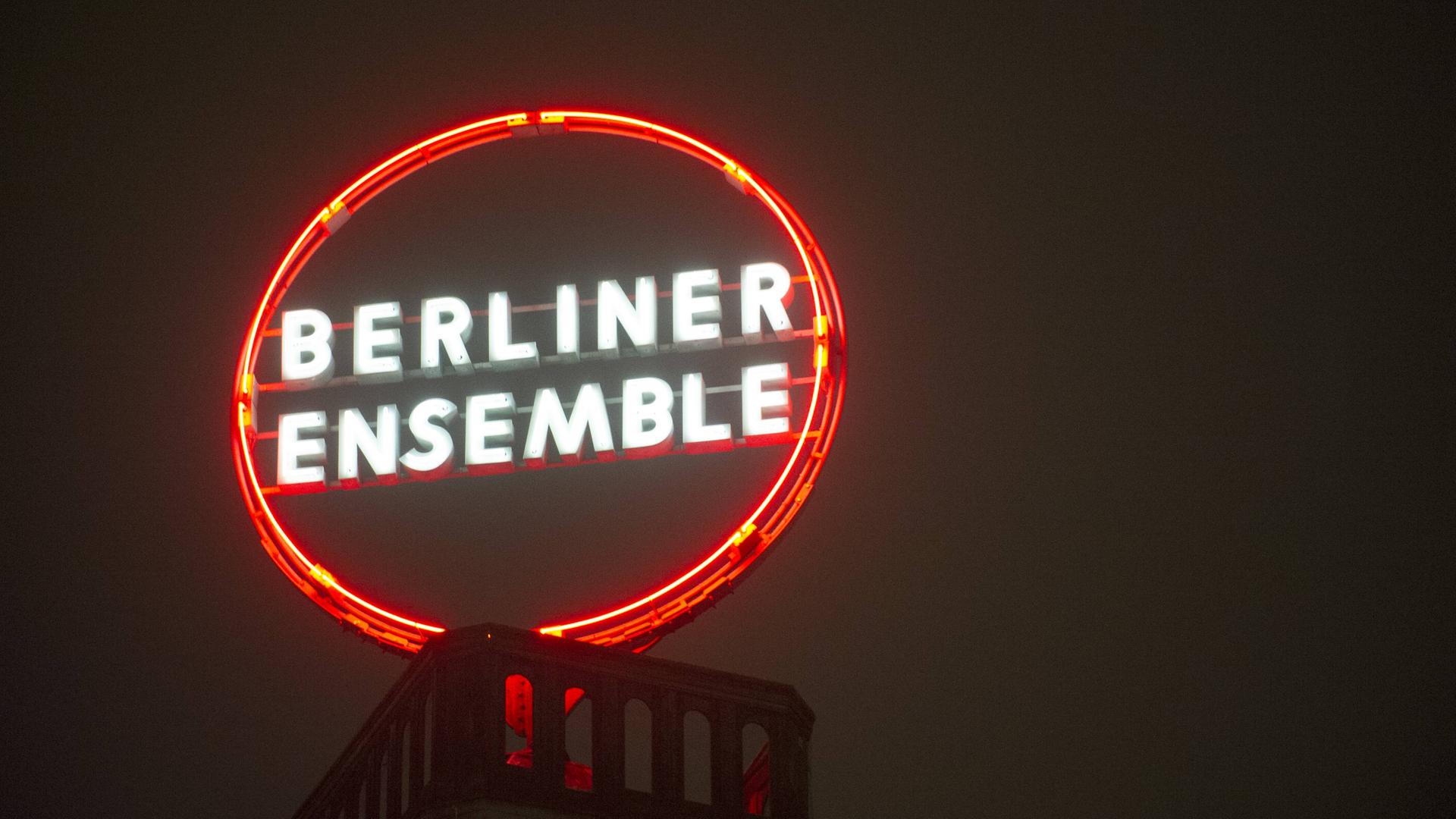

Teatri a Berlino, la vertigine della Storia

Alle città del teatro – partendo dalla nostra Milano (a breve una riedizione) – Cue Press dedica Le Guide, una collana diretta da Andrea Porcheddu. La tappa più recente è Berlino. Sostiene l’autrice, Sotera Fornaro, che proprio qui ha trovato realizzazione, nell’ultimo decennio e «con un accentuato e inarrestabile processo di estetizzazione», la «società dello spettacolo» annunciata più di cinquant’anni fa da Guy Debord. Non si può darle torto pensando che, fra le capitali europee, Berlino è quella su cui la storia recente ha operato le più importanti (e dolorose) metamorfosi. «Tutto cambia, si trasforma: da almeno venticinque anni la città si frantuma in una serie di cantieri aperti. Basta mancare un mese per trovarvi nuovi edifici, locali, punti d’attrazione. Eppure tutto si inscrive in una tradizione che resiste, non è sepolta dal nuovo look turistico della città». 3 milioni e mezzo di abitanti, 6.000 artisti, circa 500 compagnie di teatro e danza, 35 teatri o luoghi di performance. «La messa a nuovo e la ristrutturazione della Berlino di Federico II, corrisponde a una mimetizzazione della Berlino nazista». Dalla Komische Oper alla Volksbühne, dalla Staatsoper al Maksim Gorki Theater, dal Berliner Ensemble al Deutsches Theater, e ricominciando il giro, fino alla Schaubühne. Dai Landmark del centro a spazi più laterali, come i cortili di Hacke, a quelli a basso indice di integrazione, nel quartiere operaio di Neukölln. È tra queste vie ed edifici che l’autrice ci conduce, alternando passato monumentale e presente eccitante. Così la seguiamo mentre si incammina lungo la celebre Unter den Linden. Scorriamo con lei locandine e programmi di stagione. Respiriamo in quelle sale, tra quel pubblico. Sentiamo la temperatura di una città, attraversando la quale – diceva il premio Nobel Imre Kertész – «si è presi dalla vertigine assurda della Storia».

Diverse abilità, nuove vie della danza

Navigare esplorando le innumerevoli possibilità creative del corpo danzante, senza preconcetti. È questo il motore del libro curato da Andrea Porcheddu che affronta tematiche urgenti, tra le quali il rapporto tra professionismo e disabilità, dando parola proprio agli artisti.

Concepito come una pluralità di voci, l’agile volume fa propri i termini della marineria per sviluppare un viaggio innervato su dieci interviste ad altrettanti danzatori, coreografi e non solo, molti dei quali in transito al Festival Oriente Occidente.

La kermesse di Rovereto, infatti, oltre a essere il festival monografico dedicato alla danza più antico d’Italia, è attualmente impegnata nel progetto europeo Europe Beyond Access-Moving Beyond Isolation and Towards Innovation for Disabled Artists and European Audiences (2018-22) garantendo così agli artisti con disabilità spazio e possibilità creative.

Nella trattazione ampio spazio è riservato alla Candoco Dance Company, celebre ensemble inclusivo con base a Londra fondato nel 1991 da Celeste Dandeker-Arnold e Adam Bejamin ora diretto da Charlotte Darbyshire, e ai coreografi con cui la compagnia ha intessuto dialoghi creativi, come Yasmeen Godder e Javier De Frutos.

A ciò si aggiunge la riflessione della scozzese Claire Cunningham, superlativa solista che ha sviluppato un linguaggio del movimento del tutto originale.

Non mancano, però, all’appello le voci della scena nazionale come quelle di Michela Lucenti/Balletto Civile e degli autori emergenti Chiara Bersani e Aristide Rontini, i quali sottolineano l’importanza dell’accesso alla formazione, lo scambio di pratiche e le problematiche di circuitazione.

Completano il volume, una ricca iconografia a colori e una teatrografia che contempla diversi spettacoli, forse troppi, legati al tema centrale secondo dinamiche non sempre chiare.

Così Puppa aggira I giganti della montagna. Un viaggio sbalorditivo nei meandri oscuri dell’opera pirandelliana

Paolo Puppa è uno dei conoscitori più attenti e profondi dell’opera pirandelliana, a cui ha lavorato per oltre quarant’anni, senza tralasciare nulla, tanto che la sua metodologia esegetica ne viene persino condizionata e risulta perfettamente ciclica, nel senso che utilizza un testo base e, attorno a esso, costruisce la sua indagine. Ne è prova il volume, pubblicato da Cue Press: Fantasmi contro giganti. Scena e immaginario in Pirandello, la cui prima edizione risale al 1978, Patron Editore, con prefazione di Luigi Squarzina, nel quale I giganti della montagna diventano un pretesto, non solo per i continui rimandi al teatro precedente, ma anche alla novellistica, alla saggistica e alla narrativa.

È in tal senso che intendo ‘metodologia ciclica’, perché l’autore cerca di aggirare il testo in esame con continui rimandi ad altre opere e non solo, dato che questo approccio gli permette di utilizzare la multidisciplinarietà, permettendo alla sua ‘lettura’ di ricorrere, non solo alla storiografia teatrale, ma anche ai processi psicoanalitici e antropologici che sottostanno ad essa. Puppa, inoltre, fa ricorso alla categoria del viaggio, se vogliamo, a ritroso, rappresentando I giganti della montagna, l’approdo ultimo di questo viaggio che ha attraversato la dialettica tra scena pubblica e scena immaginaria, tra attore e personaggio, fino alla sua smaterializzazione ed emarginazione, in uno spazio scenico che si è alquanto dilatato anche quando ha fatto ricorso al salotto borghese che, in Pirandello, ha finito per assumere valenze metafisiche e fantasmatiche.

Il viaggio si inoltra nei meandri oscuri dell’opera pirandelliana, che Puppa cerca di decifrare, ricorrendo alle teorie di Binswanger, Freud, Jung, Lacan, rapportando le indagini sui testi teatrali con quelli della novellistica, vero e proprio laboratorio. È sbalorditiva la conoscenza che Puppa mostra di questo laboratorio in cui Pirandello esegue gli esperimenti per costruire il suo teatro, oltre che il modo con cui riesce a concatenarli.

Il lettore è messo nelle condizioni di trovarsi in una vera e proprio cosmologia, direi inedita, attraversata da tanti satelliti che la illuminano e che la discostano dalle interpretazioni precedenti.

Leggendo il testo di Puppa senti delle vibrazioni che non appartengono soltanto al materiale preso in esame, bensì alla sua prosa, una prosa d’autore che fa da pendant a quella del Puppa drammaturgo, grazie a un linguaggio perturbante che userà, successivamente, in altra sede. In questo lungo viaggio, appaiono evidenti le lacerazioni tra il teatro commerciale, il teatro capocomicale e quello creativo affidato all’immaginazione, così come risultano evidenti le divergenze tra attore e personaggio lungo un itinerario che dai guitti, che troviamo anche nei Carri di Tespi del fascismo (grandi padiglioni in strutture lignee coperte, adibiti ai comici nomadi, anticipatori del Teatro di strada di sessantottesca memoria), porta all’attore borghese, con i suoi vezzi e l’amore per l’immedesimazione, che non vuole dipendere da registi come Hinkfuss, fino all’attore marionetta che troviamo nell’Arsenale delle Apparizioni, per concludere con l’attore sciamano o mago, rappresentato da Cotrone.

Il viaggio si trasforma in fuga, in particolare dalla scena pubblica, un tempo tanto ambita, per finire in uno spazio decentrato, quello della Villa della Scalogna, spazio dell’Avanguardia, dove si sperimenta il rapporto tra l’attore in scena e l’attore in video che, nel nostro caso, è rappresentato dal muro ocra dove Cotrone proietta frammenti di immagini della Favola del figlio cambiato. Si passa, così, dal teatro come luogo in cui si mette in scena la vita e non la finzione, come nei Sei personaggi, al teatro in cui si dà voce al pubblico, come in Ciascuno a suo modo o in cui ci si ribella al regista, come in Questa sera si recita a soggetto, per scegliere lo spazio dell’immaginario che, per Artioli, è anche un immaginario cristiano, dove la vita soccombe all’Altro che non si conosce per la perdita della sua presenza e per essere diventato fantasma, onde predisporsi alla lotta contro i Giganti, nel momento in cui il senso ultimo sarà quello di non aver senso.

Beckett è già dietro l’angolo, come ha dimostrato Gabriele Lavia nella recentissima messinscena dei Giganti della montagna, con Ilse impersonata da un’eccellente Federica Di Martino.

Collegamenti

Il realismo (globale) di Milo Rau

Cos’è un autore? Cos’è il teatro mondiale? Cos’è il realismo globale?

Sono alcune delle domande a cui Milo Rau prova a rispondere nelle pagine di questo volume, che raccoglie scritti d’occasione (dalle interviste ai saggi, dai discorsi ai manifesti) composti nell’arco di un decennio.

Ne emerge non solo il ritratto di un autore fra i più controversi della nostra epoca, ma soprattutto una riflessione paradigmatica sulla funzione dell’arte nel mondo contemporaneo.

Collegamenti

Instabili e vaganti, senza fissa dimora. Ma con il mondo e la natura come palcoscenico. E con il corpo come teatro

Il volume Stracci della memoria, pubblicato da Cue Press, mi permette di fare alcune riflessioni sulla dimensione teatrale del terzo millennio, tipica di una generazione che ha scelto di rinunziare al testo come rappresentazione per accedere a un lavoro artistico capace di coinvolgere il corpo, da utilizzare per la realizzazione di un ‘progetto’. Non si tratta del teatro del corpo, inteso come corpo della parola, bensì del corpo del performer che sostituisce la parola con l’azione fisica.

Il volume di Anna Dora Dorno e Nicola Pianzola fa riferimento al lavoro svolto dalla Compagnia Instabili-Vaganti, tra il 2004 e il 2018 che già, nella denominazione, evidenzia una vocazione, comune a tante altre, che consiste nel non avere una stabilità, ovvero un luogo dove operare e nell’essere instabili in tutti i sensi, anche economicamente, tanto da andare alla ricerca di ‘residenze’, non soltanto nazionali, ma anche internazionali.

Sono, insomma, delle mine vaganti che fanno, del viaggio, un mezzo di conoscenza di altre realtà consimili, appartenenti a continenti diversi. I ‘progetti’ che ne scaturiscono sono tipici di chi va alla ricerca di avventure, soprattutto, nel campo performativo, comuni a tanti gruppi instabili e vaganti che si incontrano nei vari festival internazionali.

Come si può intuire dai loro tracciati teorici, tutti mostrano la vocazione a contrapporre l’uso del corpo a quello della voce e, ancora, l’uso estetico (coinvolgimento culturale dello spettatore) a quello sinestetico (coinvolgimento sensoriale dello spettatore). Non manca, in questi gruppi, una incontrollata presunzione, dato che pur ammettendo di conoscere e di aver studiato la tradizione dei Maestri, insistono in una ricerca troppo personalizzata, con apparati teorici che, in fondo, ripetono quanto hanno appreso dagli stessi Maestri che, in molti, non hanno conosciuto, ai quali si sono accostati leggendo le loro teorizzazioni.

Cosa hanno imparato da costoro? Per prima cosa l’uso dello spazio, non certo quello dei teatri tradizionali, bensì quello che si trova in Natura o in luoghi abbandonati, in chiese sconsacrate o nei villaggi. Si tratta di spazi non deputati che cercano di confermare la forza del ‘naturale’, da contrapporre a quella della finzione. In tutti questi gruppi, del terzo millennio, si riscontra la riattivazione di pratiche originarie che comportano una diversa concezione del Rito che mostra evidenti contatti con le operazioni già svolte dal Bahuaus, da Grotowski, da Barba, da Brook, ma anche dai nostri Leo De Berardinis e Carmelo Bene.

Altro elemento che li accomuna è l’uso della ibridazione, della interculturalità, della frammentarietà, non per nulla pubblicano le teorie di ciò che fanno, piuttosto che i testi, trattandosi, appunto, di frammenti. A costoro, non interessa un ‘ordine’, preferiscono fondere elementi diversi che si scontrano con ogni tipo di drammaturgia prestabilita, tanto da aderire a un ‘disordine’ consapevole che dovrebbe corrispondere al disordine della memoria che raccoglie ‘stracci’ del passato per costruire un processo unitario che scorre come un fiume a cui è necessario porre degli argini. Questi gruppi lavorano anni per dare unità a una molteplicità di materiale raccolto, fatta, soprattutto, di letture, anch’esse frammentarie, un po’ caotiche che alternano nozioni filosofiche con altre antropologiche che fondono, a loro volta, in teorizzazioni pro domo sua, ben sapendo che il teatro, che loro definiscono convenzionale, odia le teorizzazioni, essendo, il palcoscenico, luogo dell’azione, sia testuale che performativa.

Come se non bastasse, costoro vanno in cerca della tradizione ermetica, condita con quella alchemica, per trasformare le loro emozioni in azioni performative e dare, agli impulsi corporei, una forma pura. Le loro riflessioni, frutto di letture episodiche e non strutturali, si trasformano in materiale di Workshop, di spettacoli interattivi, per i quali, diventa determinante l’apporto di videomarker affinché performer e immagine proiettata diventino uno spazio comune.

Insomma, gli stimoli sono tanti per chi avesse voglia di leggere questo libro che racconta, anche, la storia di un progetto dal titolo emblematico: Stracci della memoria che raccoglie un materiale immenso, strutturato in una trilogia che ha una sua genesi : Il sogno della sposa e un suo ‘sviluppo’, attraverso altre tappe: La memoria della carne e Il canto dell’assenza che confluiranno in uno spettacolo unico: Il rito, sviluppo avvenuto durante i loro viaggi nelle risaie dei villaggi coreani, nelle case colorate della città del Messico, negli spostamenti da Pechino alla Patagonia, nei vari festival etc, tutti necessari per scoprire nuovi mondi, nuove maniere di relazionarsi, nuove fasi di creazione che, infine, caratterizzano una tipologia di teatro, quella tipica del terzo millennio.

Collegamenti

Anni incauti, ma con metodo

Ci sono pur sempre diverse pubblicazioni dedicate ad esperienze teatrali e ai loro protagonisti: mai abbastanza, per la verità, ma raramente è dato avere per le mani un libro polifonico come questo, un oggetto colmo di soggettività, che in qualche modo esprimono se stesse e il loro punto di vista sul circostante quasi servendosi di DOM, ovvero l’invenzione della cupola del Pilastro, come fosse una piattaforma, offerta dagli artefici della compagnia Laminarie, con quella generosità priva di precauzioni e parafulmini che si svela appunto già dal titolo, omonimo alla loro più recente stagione: gli Anni incauti.

Un titolo molto suggestivo che sembrerebbe alludere persino ad una certa sventatezza, se non fosse che risulta molto difficile definire cosi l’attitudine ponderata di Bruna Gambarelli ad osservare e fare interrogazioni, quasi fosse impossibile per lei, parlare di sé, non soltanto parlandosi addosso, ma specchiandosi nelle altrui narrazioni. Qui si va molto oltre infatti, affermando un discorso pluricentrico, in cui non necessariamente l’esperienza di Dom in quanto tale assume un valore paradigmatico, ma tutto ciò che ci sta dentro e intorno viene rappresentato, chiosato, raccontato e smontato pezzo per pezzo, senza assumere quelle cautele che di solito servono a non sporcarsi: insomma, siamo in una sorta di ciclofficina, se Ampio raggio è il titolo della pregiata rivista d’esperienze d’Arte e Politica, che costituisce l’ossatura del volume editato per i tipi di Cue Press a novembre 2019.

Anni incauti è costruito come una lettura a ritroso di un’esperienza decennale ancora in essere, il che evita il tono funerario celebrativo che a volte accompagna questa tipologia di operazioni. Rischio dribblato persino allorquando si ripropongano riflessioni di eccellenti compianti maestri e sodali quali, ad esempio, Claudio Meldolesi: il fatto è che gli interventi succedutisi in questi dieci anni di teatro e di rivista vengono ri-scelti e riletti da autori di ieri e di oggi e arricchiti di senso ulteriore, senza un nostos cui riferirsi.

La cosa sorprendente è che moltissimi scritti sono per l’appunto interviste, dibattiti svolti con un esprit de finesse ancora più spiazzante perché rivolto ad altri che DOM stesso e chi lo ha fondato, eppure si riconosce precisamente in tutti quella densità, quella materialità, quel peso specifico che sono la cifra inconfondibile di tutta la poetica e il duro lavoro scenico di Febo del Zozzo e anche la natura bruciante dell’approccio alle questioni pedagogiche da parte della Compagnia tutta. Un che di sacrale e pagano al tempo stesso si respira in certi allestimenti dei loro ed anche emerge dalle tonalità calde, ferrigne, encaustiche che dominano tutta la parte iconografica del volume: il calore dei corpi, dell’agape, delle luci soffuse, degli interni intimi, dell’energia che plasma le cose, traboccano dalle pagine, mentre i titoli dell’indice ci fanno capire come amando e scegliendo talenti, competenze, opinioni e soprattutto storie di altri, tanti altri, non necessariamente artisti ed intellettuali, non necessariamente affiliati alla grande comunità teatrale, si riesca a parlare di se stessi in maniera estremamente efficace. E soprattutto, utile.

Anni incauti potrebbe essere anche letto come un manuale, un manuale o meglio un antidoto, ad una certa stupidità dei tempi, proclamando anche la bellezza dello sguardo che non conosce e non sa, ma vuole ornare e occupare, come acutamente nota Claudia Castellucci in uno dei piccoli saggi o haiku di saggistica che compongono il libro: discorso che mette a zero le chiacchiere sulla periferia ghetto. Non si sarà mai costretti o esiliati in un posto se lo si occupa e cura con abbellimenti e pratiche, con gesti precisi e amorevoli, con parole nette, quasi affilate, come nota Marchesini nel testo più flaneur, in riferimento a Bruna. Parole che tuttavia non feriscono, neppure definiscono una per tutte o circoscrivono il senso, ma richiamano semplicemente alla necessità della responsabilità e scusate se è un poco che non è mai abbastanza, ma eccede, esagera e insiste, come rammentano titoli di spettacoli e stagioni delle nostre Laminarie.

Occupare, non significa qui trasgredire sui confini della Polis, ma risemantizzare il termine e portarlo ad un valore di limen sacro fatto per gli attraversamenti. Lo stare di Bruna e Febo, straordinario e fecondo sodalizio di arti e di vite, non è il comodo piazzarsi o l’imperiale «hic manebimus optime», ma lo stare vigile di chi ha natura nomadica e non è un caso che due mappe siano presenti all’interno del libro, la pianta del DOM, la cupola al Pilastro riabilitata e riusata cosi poieticamente prima che le rigenerazioni urbane fossero in voga, e gli itinerari dolenti di Laminarie, (che dedicò non molto tempo fa un bellissimo approfondimento anche fotografico al tema dei nuovi steccati europei), nella sua versione non stanziale, ma progettuale, lungo le rotte delle crisi e dei conflitti. Laminarie dunque e, per esempio, la Ex Jugoslavia, sempre per assumere quei ‘io c’ero e testimoniavo, portavo il mio corpo e il mio discorso’, che sta tutto dentro il pensiero di Simone Weil, figura straordinariamente mentore per Bruna Gambarelli.

Ma ci sono tante altre declinazioni di Laminarie, quella certo alta, di chi affronta l’infanzia con gli strumenti del mito e della fiaba decostruendo l’idea di una pedagogia per l’infanzia e l’adolescenza che debba ammaestrare e insegnare e intimorire, come secondo canoni assunti dalle esperienze della Societas Raffaello Sanzio, andando poi molto oltre, verso una comunità che impara dal suo crescersi, quella di Laminarie, quasi compresse, potremmo dire, ma sempre risorgenti, da un perverso incrociarsi di sbadataggini e dimenticanze della burocrazia sulle Periferie, salvo poi doverci tutti tornare sopra con alti lai, come necessario, del resto, perché nulla è dato mai per scontato e acquisito nella nostra difficile storia civile. Ci sono le Laminarie che vincono un premio UBU solo pochi anni fa per la tipologia particolare del loro lavoro sulle Periferie appunto, assolutamente culturale e non socio-assistenziale proprio perché svolto a stretto contatto con chi opera negli altri settori deputati con il rispetto dovuto alle diverse identità e funzioni. Ci sono le Laminarie che rischiano successivamente in maniera del tutto incongrua di perdere i finanziamenti ministeriali e resistono, resistono, resistono grazie ad una campagna d’amore nel Quartiere che sembra persino leggenda, nel momento in cui il clima sociale sembra brutalmente virare verso una caccia alle streghe anacronistica quanto vigliacca.

Insomma ci sono le Laminarie che avrebbero del tutto il diritto di sentirsi frustrate, appartate non per scelta, perché in effetti, un centro potrebbe essere in ogni punto della mappa, potrebbero fiaccarsi in tanto tenere la tensione, invece non se lo concedono, per il semplice fatto che c’è DOM e Dom è una residenza teatrale, ancorché eterodossa ed un posto da frequentare con naturalezza senza necessariamente definirlo. Pertanto, non deve diventare l’esperienza temporary, ma un’istituzione che fa parte di un polo cultural-artistico complessivo, che assuma le tante esperienze aggregative fatte al Pilastro e le porti a valore. La compagnia Laminarie insiste e persiste perché c’è un quartiere, dietro di lei, come forse raramente succede in Italia ad un gruppo teatrale e perché non si può mollare su una cosa viva e vitale, anche se ogni tanto tira o prende pugni nello stomaco.

Per questo si racconta la storia di Febo atleta di se stesso e scultore di spazi, (non dimentichiamo la sua formazione all’Accademia di belle Arti), di Bruna teorica e promoter insieme, animale politico in essenza e dei loro fidi collaboratori, cui ormai potremmo aggiungere le loro splendide ragazze, anche attraverso l’Archivio digitale di Comunità, una creatura di tutti e dunque anche loro. Per questo il nucleo forte di DOM, viene attraversato dai fatti tragici della Storia, come per esempio i fatti della Uno Bianca e dal grottesco leghista della cronaca di oggi, come da un fuoco che forgia continuamente.

Nello stesso tempo, l’ampio raggio della visione consente sulla pagina di parlare di fumetti e Carmelo Bene, di foto di famiglia e televisione di quartiere senza fare calderone, senza scadere mai nel pop del gran banale quotidiano, senza blandire in nulla il nazional-popolare e tenendo alta la barra del linguaggio.

Né popolari, né populisti, ma cittadini artisti tra cittadini attivi, io credo che faranno seguire molti altri anni imperfetti e rigorosi, di cimento e di prova cui sapranno trovare altri titoli prescrittivi e predittivi, come è loro cifra, del loro stare e mostrare, non per indicarci una via maestra, ma per chiamarci a non avere paura e a stare sul pezzo. Restano sul tappeto, annose e delicate questioni, adombrate dall’acuto e appassionato intervento del critico e intellettuale Massimo Marino, su cui mi sembra opportuno chiudere e nello stesso tempo tenere in sospeso fiato e idee in attesa, forse, di una capriola e di una nuova invenzione, che favorisca il riconoscimento di valore e perché no, di merito, delle esperienze, che porti ad una centralità forte, ma che personalmente sono convinta si avrà cercando e trovando ancora molti compagni di strada e di convivio che abbiano voglia ed energia di focalizzare insieme obiettivi di trasformazione possibili fuori dal piagnisteo e dal chiacchiericcio spossante e che sappiano smascherare orizzontalità fasulle o addirittura perniciose, che di fatto abitiamo smarriti perché non sappiamo, prima ancora di capire se distruggere o cambiare, percorrere e rendere sicuri e percorribili canali di navigazione tra basso e alto e viceversa e agire anche la verticalità, qualcosa, a ben vedere, di molto diverso dal verticismo.

Collegamenti

Il Pilastro e la cupola di Dom: gli anni incauti di Laminarie

Anni incauti era il titolo dell’ultima rassegna di Laminarie ed è anche quello di un libro che doveva essere presentato in questi giorni. A cura di Bruna Gambarelli, con Febo Del Zozzo anima della compagnia bolognese, ricorda i dieci anni di attività al Pilastro in modo originale. I centri sono due: L’invenzione di Dom la cupola del Pilastro (come recita il sottotitolo), lo spazio dove in questo decennio Laminarie ha operato; la rivista Ampio raggio, editata in otto numeri, più un numero 0 del 2009. Pubblicato da Cue Press, il volume (176 pp., euro 25,99) si può trovare come e-book, ma anche in librerie e biblioteche cittadine.

Ci spiega Gambarelli: «Abbiamo pensato di raccogliere i pensieri che hanno attraversato questi anni di impegno sui fronti del teatro contemporaneo, del territorio, dell’attività teatrale per i bambini, del cinema, della ricerca sulle memorie della zona».

Questi pensieri si erano sviluppati soprattutto intorno alla rivista: «Non volevamo compilare noi una specie di ‘best off’. Allora abbiamo chiesto a critici, studiosi, artisti, che in questi anni hanno incrociato il nostro lavoro e scritto per Ampio raggio, di segnalarci articoli che secondo loro bisognava ripubblicare. Poi abbiamo domandato loro di regalarci qualche intervento originale, o di permetterci di ripubblicare loro testi che ritenevano importanti rispetto ai temi che abbiamo trattato».

Nel libro si trova di tutto, con discorde coerenza: interventi del geografo Franco Farinelli, del critico teatrale Gianni Manzella, del direttore della Cineteca Gian Luca Farinelli e di altri; riprese di articoli su vari argomenti, dai graphic novel di Andrea Bruno alle musiche di Joe Hisashi per i film di Miyazaki e di Kitano, da una storia del Pilastro tracciata da uno dei primi abitanti, Oscar De Pauli, a discussioni su centro e periferia, a un’intervista a Gianni Berengo Gardin circa il lavoro fotografico sulle famiglie del quartiere, del maggio 2010.

Il primo intervento che si legge, di Maria Concetta Sala, insegnate, studiosa di problemi della città, bene colloca l’intervento di Laminarie tra «meravìglia» e «granelli di sabbia», ossia tra avventura della scoperta e rifiuto di ima riproduzióne pacificata delle cose. Cinque sono le «virtù» di Laminarie, evidenzia la studiosa: combinare spettacoli, concerti, incontri, residenze, letture pubbliche, tra diversi ambiti disciplinari e teatro contemporaneo; superare la fratture tra arte e vissuto, soprattutto con gli interventi per i ragazzi; abitare un teatro facendolo interagire con il territorio; dialogare con la «necessità», ossia con gli abitanti, dando loro la voce con diversi mezzi; partire, rapportando tutte queste pratiche radicate con altre esperienze e altri artisti, a livello nazionale e internazionale.